Why Linux containers matter for the Internet of Things

Zach Walchuk of resin.io

Linux containers have become a standard tool in cloud development and deployment workflows. The benefits are numerous, including portability across platforms, minimal overhead, and more control for developers over how their code runs.

The popularity of containers continues to grow:Docker, an open source container engine, has seen especially high traction, with one study showing a 40% increase in adoption over the course of a year. It’s clear that containers matter, and we think they matter even more for the Internet of Things, says Zach Walchuk technical content lead at resin.io.

At resin.io, we believe that Linux containers mark the arrival of the first practical virtualisation technology for the embedded world. Running Docker on a Raspberry Pi gives you most of the benefits of running Docker in the cloud, while enabling additional features that are crucial to the success of any IoT project: isolated application failures, efficient updates, and a flexible yet familiar workflow.

What are Linux Containers?

Virtualisation is an important concept in the world of software. Software is built in a modular fashion, so that any one application may have a number of specific application, operating system, or hardware dependencies. Virtualisation puts a layer between the base hardware and the software running on it, allowing a variety of applications to be run side-by-side on the same device with each application given exactly the resources it needs.

This level of abstraction makes life easier for the application user, but it also makes life easier for the application developer. The core code of an application doesn’t have to change based on the platform it is intended for, as it can be wrapped up with the appropriate requirements when needed.

Prior to Linux containers, available virtualisation technologies were not ideal for wide use in IoT devices. Technologies like OSGi and Android’s Dalvik VM engine are language specific, not useful for applications written in anything other than Java. System virtual machines (VMs), which fully emulate specific hardware configurations, have two major drawbacks. The first, and most obvious, is the overhead required to run them.

Embedded devices have limited storage space, computing power, and bandwidth, and increasing these resources to handle unnecessary overhead increases the per-device cost without adding any real benefit. The other roadblock is the level of virtualisation system VMs provide. For embedded devices, it is expected that an application will need to access the hardware of the device, whether this means sensors, displays, or anything else. Abstracting away the hardware solves one problem while creating another.

Linux containers provide OS-level virtualisation. The hardware and OS kernel are shared between processes, saving the overhead costs seen with system VMs, while each container can be run with its own Linux distribution, configuration, and applications. By standardising the operating system, this approach to virtualisation allows applications to be built for use across a variety of device types, while still providing access to device-specific hardware. In addition, providing a layer between the device and application runtimes permits a few features that are critical for IoT devices.

Why Linux containers for the Internet of Things?

- Isolated application failures

In the world of remote, internet-connected devices, downtime is especially costly. Unlike a cloud instance, if a device goes down, you can’t simply spin up another to replace it. That device might be a drone, a car, a smart lock in someone’s home, or a sensor station in an oil field. IoT devices are often physically inaccessible, so manual reboots aren’t easy. Containers make it possible to recover when something goes wrong.

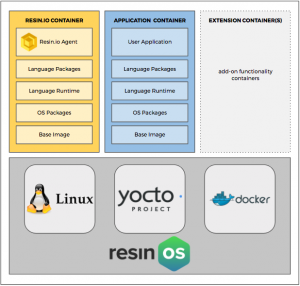

How does this work? It’s essentially a matter of separating the core operations of the device from the application layer, ensuring that an application failure won’t affect the device’s ability to communicate on the network. For example, all resin.io devices run resinOS, a bare-bones host OS that includes a Docker container engine:

This host OS manages two containers: one running the supervisor, an agent that ensures the device is running properly and can connect to resin.io, and the other running the user application, complete with its own base OS. The host OS interfaces with the hardware watchdog, ensuring a reboot happens if there’s any issue with the low-level software. In the end, this makes anything above that level an application issue that can be resolved remotely.

- Efficient updates

Another advantage provided by containers is the ability to better manage updates, including a lower frequency of downtimes and reduced use of disk space. As an example, let’s take a look at how updates are handled by resinOS. The traditional approach for applying updates with the option of a fallback is an A/B partition strategy. This splits the drive in two, with one half remaining unused.

Updates can be downloaded and installed in the empty partition without removing the active OS and without losing connection to the network. If there are any issues switching to the updated OS, the device can be rebooted with the last working version, greatly reducing the chance it is lost to the network. With resinOS, most of what is needed to run a user application is packaged in a Docker container and can be updated without any downtime. This reduces the frequency of updates required for the host OS. When a host OS update does need to be made, an A/B partition strategy is still used, but the minimal footprint of the host OS allows the update partition to be much smaller.

- A flexible yet familiar workflow

Containers play a large role in bridging the gap between cloud and embedded workflows. Linux is a widely used and highly customisable operating system, and Linux containers provide a standard core set of features while still giving developers the freedom to choose the tools, libraries, and configurations they are already familiar with. This flexibility is expected by cloud developers, and extending it to embedded devices enables more developers to build and support IoT projects. By aligning the underlying technology across cloud and edge devices, containers reduce the friction for developers and organisations supporting hybrid workflows.

What’s missing?

Linux containers provide clear advantages for IoT use cases, but there are still some things to consider before the technology is fit for use on remote devices. Luckily, an open source project like Docker allows the underlying application to be treated as a platform, leaving room for use-case specific modifications. And public repositories like Docker Hub allow container images to be easily shared, making for a robust application ecosystem.

Here are a few of the improvements resin.io has made to adapt Docker to IoT use cases:

- Support for a wide variety of devices

Docker out of the box is oriented heavily towards use in cloud servers and desktop machines. To be useful in the world of embedded devices, it needs to run on a wider variety of devices, each with its own specific hardware requirements. To account for this, resin.io releases distinct host OS images for over a dozen supported devices. While the host OS has the same core functionality across devices, specific considerations are taken into account to allow the full capabilities of the device to be utilised.

- Binary deltas

Docker uses a layer system to reduce the size and build time of updates. When an image is updated, only the layers that have been modified need to be changed. This works well enough in situations with reliable network connectivity, but it still requires more bandwidth than is ideal for remote devices on, say, 3G cellular networks. Resin.io has the option for delta updates—a full binary diff is made between the built container and the running container, and only the differences are downloaded to the device. In typical scenarios, we have observed 10-100x improvements in the bandwidth required to perform the same update.

- Smaller container engine

The standard Docker container engine contains some features that apply mostly to cloud use cases. With balena, our custom, Docker-compatible container engine, we’ve removed many of these, making a container engine that is less than 25 MB, as compared to over 100 MB for the standard engine. When bandwidth and storage space are highly constrained resources, this size difference matters.

- Resiliency to power and network failures

Operating expectations are quite different for remote devices and cloud servers. Power and network failures are far more frequent for embedded devices, and the software running on these devices needs to be resilient to these events. ResinOS manages containers in a way that takes this into account, including special considerations for the container lifecycle when power may be suddenly cut as well as procedures for updates over unreliable networks.

The author of this blog is Zach Walchuk technical content lead at resin.io

Comment on this article below or via Twitter @IoTGN