A “common security model” against typical hazards in the IoT

Rob Black, senior director of ProductManagement, ThingWorx

Up until now individuals have generally been using a dedicated computer for work; now, however, the Internet of Things (IoT), with billions of networked devices that are for the most part not monitored by humans, presents enormous inherent security risks.

The endless number and the different types of potential targets of attack in the IoT alone, associated with a lack of human supervision, prevent common safety methods from being used. In addition, the types of devices that are now connected to the Internet, such as cars, electric generators and water supply pumps, bear the potential for real damage in the event of a successful attack.

The attack on the power supply network in Ukraine at the end of 2015 was a foretaste of the threats to networked devices. In that instance, 30 sub-areas were offline and over 230,000 households and offices were in the dark for up to six hours. The attackers had even modified the firmware of critical equipment so that it could no longer be operated remotely and isolating switches and other devices had to be controlled manually for months afterwards, says Rob Black, senior director of Product Management at ThingWorx.

In comparison to clouds, for which there are now well defined security models and limited entry points, the IoT presents a much wider attack target due to the different device types, operating systems and protocols alone.

In terms of user management in the cloud, access is usually only granted to a specific person for a specific programme; IoT devices, however, require a significantly more complex authorisation and rights model. IoT devices can authenticate themselves autonomously as a person or on behalf of a person.

Some companies are aware of this danger but still see no urgency to act accordingly because they are still not using IoT applications on a large scale. But do they really know how many of their devices are already connected to the Internet and are therefore exposed to possible attacks?

The search engine Shodan, which scours the Internet for networked devices, has already categorised 500 million networked devices, including control systems for factories, ice hockey rinks, car washes, traffic lights, safety cameras and even a nuclear power plant. Most of these devices are connected to the Internet via an internal application from the manufacturer or a third party.

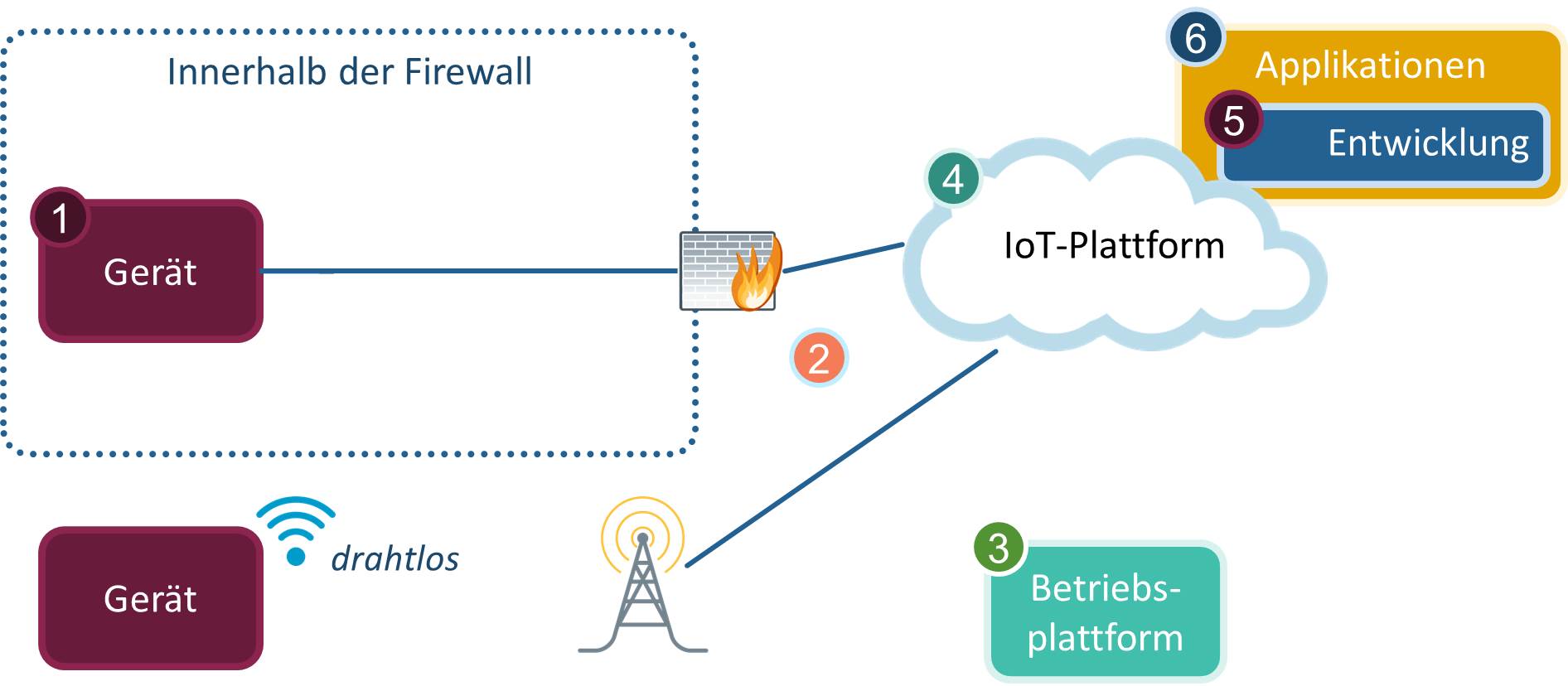

Figure 1: IoT security architecture

The majority of these devices have only very limited security functions. In many cases, not even a password is required to connect to the device; often “Admin” is the user name and “1234” is the password. 70% of the devices also communicate in text format, which makes attacks easy, even if the passwords used are a bit more secure.

Millions of devices also use very outdated software versions – with serious, well-known weaknesses. The question to many companies, therefore, is not whether they want to start an IoT project; the question is how they want to administer and secure existing – partially unknown – IoT devices.

There is currently no comprehensive security model for the IoT. However, take the security architecture shown in Figure 1 can be taken as a basis.

Here, the different elements and their interactions in the IoT are highlighted:

- The device is a real-world object connected to the network

- The network infrastructure connects devices to the IoT platform

- The operating platform makes the infrastructure for the application available

- The IoT platform is a suite of components which communicates with the devices, enables management of the devices, and runs an application programme

- Development refers to the process that is used to implement the IoT application,

- Applications create added business value by monitoring, administering and controlling the networked devices.

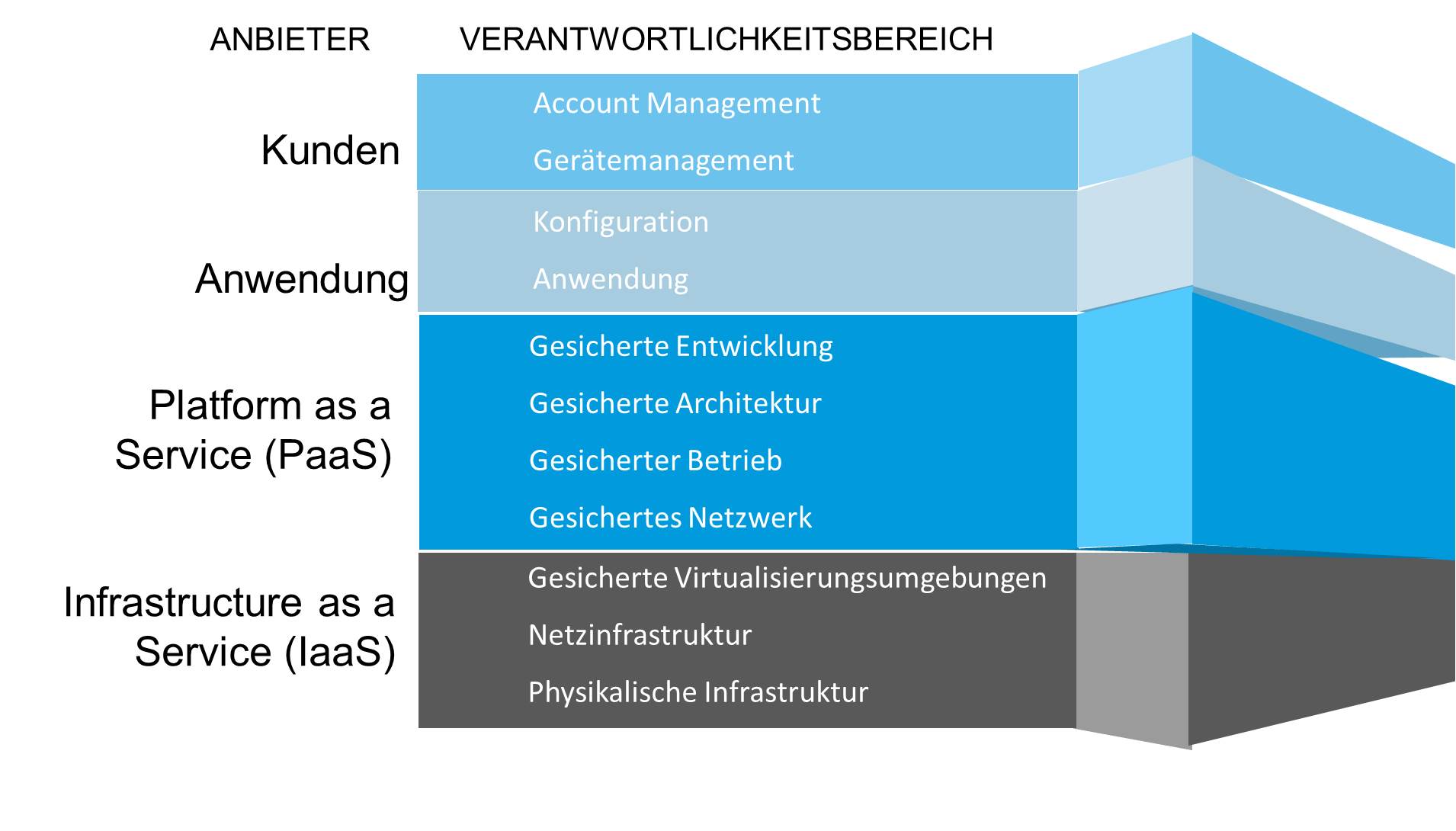

The common security model presented in Figure 2 explains how responsibility for security in the IoT should be divided between the various stakeholders. Starting from the top, the customer is responsible for protecting the various devices from unauthorised access and for managing the user accounts.

The IoT platform can make this task easier through integrated displays and rights which can be used without coding. For example, regions, departments or locations can be defined and users receive access to objects in their own region but not to objects from other regions. Functional roles can also be created within an organisation, such as “Service Manager”. The role of “Service Manager” can then be assigned to new users who automatically receive all rights assigned to this role.

Figure 2: Common security model for the IoT

Ideally, with the help of a connection server, the IoT platform would offer the option to work in a “demilitarised zone” (DMZ) while the platform itself is located within the firewall. If the IoT platform lies within the internal network, even the most determined attacks would be more difficult. With a good network concept, organisations can better protect their IoT infrastructure.

The leading platforms offer appropriate tools which application developer can use to observe best practices such as the Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP) Top 10. This was developed to avoid easily exploitable weaknesses in web applications. The “SQL injection” is among the top 10 problems. The IoT platform can prevent this attack opportunity by parameterising input and stopping direct SQL queries.

However, some of the responsibility for IoT security lies in the hands of the developer. Via the Transport Layer Security Protocol (TLS), most IoT platforms offer the ability to encrypt communication with the devices. This must of course be activated by the developer.

Regardless of how well safety has been taken into account in the development of the application, there will always be attack opportunities and, therefore, it is crucial to implement a process in which each layer can be repeatedly updated to the latest version of the protective mechanisms.

An IoT platform should therefore offer integrated software and content management functions that support the automatic distribution of updates. The more sophisticated platforms also include options for how updates should be distributed. This means, for example, that you can import and test these options with a small number of devices initially before running a general update of all objects.

A common security model with these and numerous other functions simplifies the development and implementation process for IoT applications. You can therefore optimise the performance of the widely dispersed fleet of devices and at the same time, ensure protection against unauthorised or malevolent use.

The author of this blog is Rob Black, senior director of Product Management at ThingWorx

Comment on this article below or via Twitter @IoTGN